Driving to Maynardville

Most people in my family asked, “Maynardville where? Why in the world are you going there?”, which of course required a long answer. Here is the shortest version I can manage. Actually, it isn’t very short.

Not long ago, looking at research material online, my attention turned to records from the Library of Congress and the National Archives that were made during the Great Depression. Many of them were stunning photos taken by celebrated photographers like Dorthea Lange, Carl Mydans, Ben Shan and Arthur Rothstein. There were hundreds of these pictures, taken from all over the United States, Puerto Rico and some Pacific Islands.

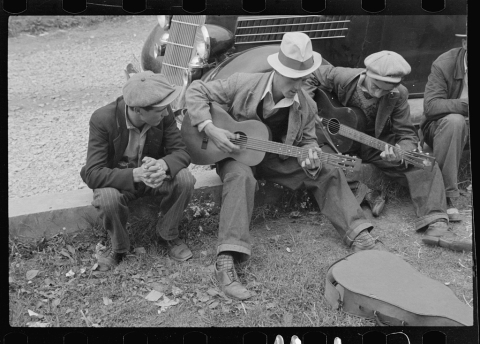

It soon occurred to me that an unusually high percentage of these pictures were taken in Tennessee. There were dozens from a farm homestead project called “Skyline Farms” in southern Tennessee, north of Scottsboro, AL, and even more from two locations near Crossville, TN; the town and a large settlement known as “Cumberland Homesteads”, which the First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visits in one of the photos. This one was obviously a crown jewel among the RA’s projects. And there’s Murfreesboro, Camden, Huntingdon, not counting a copper mine strike in the community of Ducktown. And finally there’s Maynardville, which also happens to be the County Seat. The pictures were taken in Maynardville in October 1935; they stood out from those taken in other locations because of their unusual clarity, and for the appearance of the subjects, which generally reflected a sense of independence, good health, pleasant disposition and community identity. I keep wondering who these people are, whose close-up photos revealed so much so long ago.

The Resettlement Administration, I learned, had been formed in 1935 to help displaced farmers, and built seven giant projects in states from South Carolina to New Mexico. One of the largest of these settlements was Cumberland Homesteads, in Tennessee. They included tens of thousands of acres of land, some of which was tilled, and new homes from families. A settlement farmer was typically given 20 to 50 acres, a house, equipment and money to get started. The program also involved small grants and loans.

Thus what we have is a collection of stunning photographs, detailed records of the participants of the ambitious Resettlement Administration (located in the National Archives in College Park, MD and the National Agricultural Library nearby), tons of publicly available research material, including Census, academic studies, print media, primary source historical records and government other agency records. In addition to all that, the small town of Maynardville happens to be gifted with generations of descendants who are keenly aware of the mark their parents and grandparents have made, the places, the landmarks, and have maintained a robust and revelatory narrative of local history, which is most notably reflected in the Historic Union County online newsletter. An afternoon spent with a lady who taught school in Maynardville for 47 years, Wanda Cox, left me realizing that I had known nothing whatsoever about that county, its history, or its people. Any work professing to assess the impact of a major federal initiative 80 years ago would therefore have to be validated with personal accounts and perspectives of families who actually experienced it.

The original basis of my research questions had always been, to what extent did the Resettlement Administration actually help rural Americans? It would naturally follow that one would have to define “help” and attempt to find a realistic set of measures to use.

One study I especially like compares seven large Resettlement projects being developed during that time; it was written in 1938, and even made reference to future studies as the program unfolded. I have not found those other studies yet. Here the authors, C.P. Loomis and D.M. Davidson, Jr., talked about the concept of measuring the quality of life for rural Americans, and it is an ideal I will maintain. They write,

“It has long been recognized that the problem of changing a family's level of living cannot be considered exclusively from the standpoint of the individual family. The level of living for any family as a production and consumption or social-participating unit is definitely a function of the relationship of that family to other individuals and other families in the community. Consequently, it has frequently been maintained that the community should be the smallest unit to be considered in any effort to alter living conditions”.

In addition to looking at a family’s membership of a community, they also emphasize one key tenant in the RA’s goal, home/farm ownership:

“When possible a farmer or part time farmer should work on a farm he could call his own. Ownership, it was maintained, made for stability because it gave the owner status in the community and contributed toward a more abundant life. To these and other ends resettlement were initiated by the Subsistence Homestead and by the Resettlement and Emergency Relief Administration. To be completed and carried on by the Works Progress and the Farm Security Administration.”

Standards of Living of the Residents of Seven Rural Resettlement Communities by C.P. Loomis and D.M. Davidson, Jr.

Thus studies like this one make it easier to find an empirical, measurable basis to compare the outcomes of people who participated in this program with people who didn’t. Combined with primary source narratives that are still remembered and known, I think that the end result will have a greater degree of clarity and relevance than any dry report of financial numbers.

Looking at the size and scope of the project farms, each of which included hundreds of families, it becomes vital that a methodology be developed that makes sense, both in terms of gathering available data and using it to present a truthful narrative.

Getting the sense of being buried alive in tons of information ranging from the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Resettlement Administration, the Farm Security Administration, and a few individuals who created something called country music, there was nothing else to do but to actually go there. From my perspective, the location of Maynardville, Tennessee was close to the geographic center of major developments such as Crossville, Cumberland Homesteads, Skyline Farms, and Penderlea Farms anyway. From where I live in Winston-Salem it’s only about four and a half hours, assuming the car is running well, or two and a half hours, if I test the outer mechanical limits of the Camaro and get really lucky.

So it turns out that when I got out of my car I parked on 120 Court Street, I was standing a few feet from the storied Thunder Road. A whole constellation of stories of bootleggers, cops, fast cars, liars, rogues and saints was awaiting, But how much can any one person assimilate? I am no Borg.

It also turned out that, even though I didn’t know it at first, I had some powerful allies. First there was Chantay Collins, Director of the Maynardville Public Library. As soon as she found out what I was doing, she made a phone call and then said to me, “Get in the car. There’s someone you need to meet.” A few minutes later we were in the home of everybody’s 7th grade teacher, Wanda Cox. After teaching 47 years, she had turned her attention to local history. As we met, Ms. Cox arranged three chairs close together, and said, “So you want to know about Union County...” and off she went, through stories, families, leaders, pictures. Wanda Cox didn’t even look or sound old--she is timeless; it was like listening to a history class exactly as it had been presented decades ago.

Wanda laughed out loud when I greeted Ronnie Mincey as “Doctor” (because he is); And I’m pretty sure she remembers every single student she had. Like Chantay, Ronnie had dropped everything he was doing to show me everything I wanted to see and answer every question I had to ask. The problem was I didn’t know every question that needed to be asked, and I didn't know where to look, and unfortunately I just didn’t have the time to see everything that needed to be seen. Not by a long shot.

So driving 274 miles to a town in Tennessee I had never been to turned out to be a good idea; my instincts served me well. The time spent there was helpful beyond my ability to express, but it is clear to me that future visits there and to other locations in Tennessee will have to follow.

New project name: New Deal for Rural America--1935-1940

- Log in to post comments