The Days of Tobacco

Like most people of my age from this rural area, I occasionally worked in tobacco. My start was perhaps different than most, however. I was "employed" by my school teacher father in the summers to help him measure fields for insurance companies that then may assess their worth in the event of hail storms and the like. And as a teen, I was sometimes employed by local farmers to cut or hang tobacco. As our culture has changed, so too has our production of tobacco as a cash crop. I rarely see tobacco fields now, and it sometimes makes me a little nostalgic or even sad.

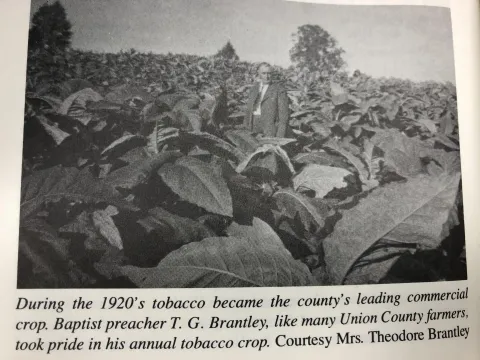

"Of Hearth And Hoe" examines Union County's connection with tobacco in the early part of the 20th century. Most Union Countians farmed and the majority, two out of three, counted their wealth in the land they owned. Farms were small, with the average size during the late nineteenth century being about 200 acres.

"Although small patches of tobacco had been grown and hauled to Chattanooga by flatboat, it was not until 1922 that a few adventurous farmers began to experiment with tobacco as a cash crop. The arrival of the Dean Brothers-John Harvey and James Wallace- at Knoxville from Middle Tennessee stimulated farmers to produce tobacco for sale. As a result of the brothers' work with the UT School of Agriculture, an effort was made to encourage East Tennessee farmers to produce burly tobacco. The Dean Brothers interest in tobacco for East Tennessee growers was in the sale of fertilizer. In the fall of 1922, the brothers rented a building at Chilhowee Park and opened a warehouse to receive the crop. Union County producers of tobacco made up one-fourth of the poundage sold in any one year at Dean Planters Warehouse."

"With the growing of burley in Union County on the increase, suitable curing barns were necessary. Over the decades following the introduction of burley growing in 1922, curing barns were constructed throughout the county and oak lumber was in great demand. Some barns were five-tier structures with the interior arranged so that tobacco could be hung on sticks. Few farmers used artificial curing methods, preferring instead to give the tobacco time to dry out. Producing tobacco was almost a year-round job. While the seedbeds sprouted and grew, growers prepared their fields.The best land on the farm was chosen for the tobacco allotment and manure was worked into the soil. At transplanting time rows were plowed, fertilizer distributed and hills prepared for setting. If the month of May produced warm rains, farmers pulled plants from their beds and, using a sharpened stick, made a hole and set the plant. If the season was dry the field was prepared and setting was done in the same manner, except that water was, in an arduous and time-consuming fashion, hauled to the field."

"During the growing season, the crop was plowed and hoed and additional nutrients were added. By July the plants were over six feet tall and had 'headed', or bloomed out; the flower was broken or cut away to encourage the growth of larger leaves. At the height of the growing season the tobacco began to lose its green color and take on a golden hue, a sign that it was ripening and would soon need cutting. Tobacco barns were put in shape, knives and spears sharpened, and sticks hauled to the fields. The sticks, approximately one inch in diameter and six feet long, were either stood on end or driven a few inches into the ground. A metal spear was placed on top and the tobacco was cut and the stalks speared onto the stick. The tobacco sticks were then hauled to the barn and hung to the top tier or lifted by rope or pulley. Each stick was spaced so that sufficient air could pass through the barn during the curing season."

"When the leaves had dried, they were ready to be 'handed' or stripped from the stalk and divided into grades. Most farmers had six grades. The lower leaves were called 'lugs.' The poorest of these went into one grade while the better leaves made up the second grade. The longer and better leaves grew from the center stalk. Called the leaf, these usually fell into two categories: 'rare' or golden leaf and the upper, redder leaf, called 'long-red.' The top leaves were placed in a group called 'short-red' and 'tips.' Each grade was kept separate and, at the warehouse, was placed on baskets arranged in rows beginning with the poorer grades. This gave buyers the opportunity to pass down the rows and view the whole crop. Bottom and top grades usually sold at a lower price than the center leaves."

"During the 1920's, 1930's, and 1940's many farm families waited anxiously to hear the 'sing-song' of the auctioneer as he was followed by buyers down the aisles of baskets of fine tobacco. Money from the tobacco crop made the mortgage or car payment, or bought new farm equipment, furniture, and clothing. Excitement generated by the annual visit to the tobacco warehouse was often repeated in other trips to sell farm produce during the harvest season. Most young men learned the ways of the 'big city' by accompanying their fathers or other relatives to Knoxville on market trips."

"Many tobacco farmers learned the best growing methods by trial and error. Often farmers tried to produce a crop without proper field selection, manure or fertilizer- a method which resulted in a poor and a small yield. Troy Buckner noted that Haulk Cox 'took his crop to Dean Planters one year. The warehouse charged 25 cents for the use of their baskets and a 4 percent commission on each crop sold. When Haulk went to settle the account with Dean Planters he owed them 40 cents'."

"During the early years of tobacco growing there were no government controls and farmers produced as many pounds as they wished. The best year for tobacco farmers was 1928, when the price was $32.50 per hundred weight, with 3,973,084 pounds sold. In 1930, the price declined as farmers hauled a record 7,305,924 pounds to Dean Planters Warehouse, receiving an average of $19.05 per hundred weight. Hoping that the price might stabilize in 1931, farmers again overproduced. In 1933 10,287,265 pounds crossed the scales, flooding the market and driving down prices further. Government controls imposed under the AAA, approved on May 12,1933, attempted to end over-production. Farmers were allotted acreage depending on the number of pounds sold the three previous years and the size of the farm."

We have all seen the decline of tobacco production in Union County as the 20th century closed and the new millennium began. Fewer smokers and more regulations and restrictions have all but ended tobacco growing. Crops come and go as society changes. Small farms, often generational family farms, are being lost. We are still a rural county, but have changed and will continue to do so. It does, as with the loss of tobacco fields, sometimes give me a sense of nostalgia and even a sense of loss.

- Log in to post comments

Tennessee Tobacco Farming

Hi Joel

Just a short note to say how much I enjoyed the article you wrote about tobacco farming in East Tennessee. I recently relocated to Knoxville from New York where I lived my whole life. As a Boomer, I decided many years ago to quit my smoking habit but when I would buy my cigarettes in New York City I gave little thought to where that tobacco came from! This was truly a wonderful read, thank you and Merry Christmas to you and your family! Linda Fitzpatrick

Thank you for your kind words

Thank you for your kind words.