Are You Afraid of the Dark?

Back in the 1930s, a guy who went by the extraordinarily fun-to-say name of Fritz Zwicky said something that made everyone think he was nuts. Fritz was a Swiss astronomer who, while peering into the depths of the inky canopy over Pasadena, California, saw something that made him look away from his telescope’s eyepiece, grind his fists into his eyes to clear them, return his gaze to the stars, and gasp in disbelief.

Zwicky was studying a large group of over 1,000 galaxies (yes, I said “galaxies”, not just "stars") called the Coma Cluster. He was particularly interested in the movement of these massive stellar neighborhoods among each other. Something didn’t add up. The way the galaxies danced should have resulted in their demise in the form of flying apart in all directions. Something Zwicky could not account for was holding them together. Some force was at work. Well, the only force plausible for such a task is gravity – and there was nothing in Fritz’s view to account for it. He was left with a choice between two equally disturbing possibilities. Either something very massive (and yet completely invisible) was exerting gravitation force upon the Coma Cluster or else all of science had the facts about how gravity works completely wrong. Given the expanse of experimental scientific evidence in support of the latter, Fritz was force to conclude the former. Something was out there.

Zwicky made up a term to describe this “something”. He called it “dunkle Materie“, or “dark matter”. As it turns out, a great amount of dark matter would be required to account for Zwicky’s observations – a really, really, enormous, great amount. Did that torrent of superfluous adjectives effectively establish my point? No? Then how about this. Fully 80% of the entire universe is now thought to be dark matter – invisible, undetectable, unfathomable, indescribable and apart from any definition of any substance known to current science. (There I go with the adjectives again.) That 80% number is far from universally accepted. Scientists love to argue about things they can't pin down. It's part of what makes them great scientists to begin with.

None of Fritz’s contemporaries, sadly, wanted to believe in this mountain of galactic fairy dust the Swiss stargazer was going on about. He was the subject of a lot of ridicule and scorn about it. Despite having a brain the size of a planet and holding claim to the term “supernova” along with over fifty patents related to pioneering work in jet engines, Zwicky never had his dark matter talk taken seriously.

Until, along came Vera.

Vera Rubin, possessing a cranium packed as tightly as Fritz Zwicky’s, slung a pretty mean telescope herself. Bent on tracking the velocity of stars swirling around the Andromeda Galaxy’s center in 1968, she noticed a phenomenon similar to the one old Fritz yammered on about three decades prior. The stars at the farthest edges of Andromeda were traveling at the same velocity as the ones at the center. The gravitational forces on these distant stars should have torn them apart millennia ago. Yet, there they were, humming along in their blissful dance. Fritz Zwicky’s “something” was clearly at work.

Rubin kept chasing. Perhaps she thought that if she was able to amass enough evidence, she would gain more credibility than Zwicky. After all, repeatability is the hallmark of any successful experiment. So, she plotted the stars from many galaxies over the following years. All the data pointed to the same conclusion. Dark matter is real. Dark matter is everywhere. There is way more dark matter than regular, everyday matter that we can see and touch. Rubin’s work was hard to ignore, although many tried. The 1960s were not exactly a time when women were welcome in all scientific circles. Efforts were made to discount, minimize or detract from her findings, but facts are pesky things. They don’t go away. They accumulate until their weight breaks down even the most persistent prejudices. It took a lot of persistent hard work, but Vera Rubin is now enshrined among the most brilliant and important astronomers in all of history. She was elected to the National Academy of Science in 1981 and awarded the National Medal of Science in 1993. She was overlooked for the Nobel Prize, but a mountain range on Mars and an asteroid have both been graced with her name. When she died in 2016, the 88-year-old left four inspired grandchildren, each holding doctorate degrees in the sciences.

So, there you have it. That’s the short history of dark matter, from great-uncle Fritz to the woman who could arguably be called the subject’s mother. But what exactly is dark matter? No one knows. The evidence of its existence is overwhelming. We know it’s there. We just don’t know what it is or how to detect it. It’s likely that it is comprised of subatomic particles the likes of which we have yet to discover and currently cannot even imagine. The fact that we have no clue about the nature of something that is several times more abundant than things we have some inkling about is incredibly daunting. It shines the spotlight of humility on our hubris. It exposes us for what we truly are – a tiny part of a massive universe whose surface we have not even begun to scratch.

This article was written by Tilmer Wright, Jr. Tilmer is an IT professional with over thirty years of experience wrestling with technology and a proud member of the Authors Guild of Tennessee. In his spare time, he writes books. His second novel, The Bit Dance is a cautionary tale about what can happen when technology runs away from its creators. You can find links to Tilmer’s books at the following location: https://www.amazon.com/Tilmer-Wright/e/B00DVKGG4K%3Fref=dbs_a_mng_rwt_s…

His author information web site is here: http://www.tilmerwrightjr.com/

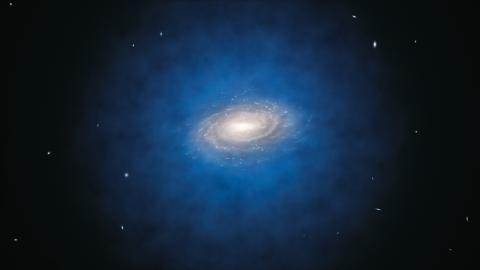

The illustration of the Milky Way Galaxy surrounded by a hypothetical halo of dark matter is used under the Creative Commons license. The work has not been modified in any way. The original may be found here: http://www.eso.org/public/images/eso1217a/ . Creative Commons license info and attribution: ESO/L. Calçada [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]

- Log in to post comments